Goff Family History - Part 2

Harriet Smith Goff

Introduction

This account, written by Gertrude Hardcastle Beckstead, granddaughter of Harriet Smith Goff, is as she remembered her grandmother and grandmother’s children.

Narrative

Grandmother Goff was the mother of fourteen children. Two boys, Henry and William, died in infancy before she left England to come to the United States.

Two baby girls, Sarah and Rachael, also died in infancy after she reached Utah. Six daughters grew up into fine women. Tom Goff’s daughters were considered very good-looking girls – each being so different in looks and personality.

Mary Ann, the eldest, was beautiful, with dark wavy hair, large blue eyes, and peaches-and-cream complexion. She had strict Victorian ways and was very conservative. There was never any wavering of moral standards for her. She walked the straight and narrow path and demanded of her family to do likewise.

Next came Ruth, the exact opposite of Mary in many ways. She was just as good looking as Mary. Her clear olive skin, dark hair and eyes belied the easy-going, cheerful, light-hearted person that she was. She was generous to a fault, readily sharing all that she had with others.

My mother, Naomi, came next; the redhead of the family. She was good and kind and almost meek. Her red hair was complimented by light freckles, blue eyes, soft mouth, soft low voice and a sincere humble attitude toward life. She was a natural born teacher, always exemplifying the teaching of her children by little stories that left an impression on the mind that remained with her children always. For example, we had a calendar hanging on the wall of the kitchen. Above the numerals on the calendar was a colored print picture of a ship about to set sail on the blue sea. The sailors were rolling up the anchor, everything being in readiness to start on the voyage. One winter evening as we all sat in the kitchen, one of us remarked about the ship and mother said, “You know my children, that picture tells me a story. Shall I tell you what I see there? To me, that big blue sea represents the sea of life. The ship is ready to start out on a long journey, which means the journey of life. The sailors are bringing up the anchor, which means our religion. As the anchor keeps the ship steered on its course, so does our religion steer us on the right path if we think of the anchor as a safeguard to us on our journey through life here on the earth.” I was about seven or eight years old at that time. Yet I have never forgotten that little story.

Next we have Tamer; dear, high-spirited, beautiful Tamer. Eyes and hair a dark brown, golden glints on her hair, eyes that could be soft and luminous when she showed her love for anyone, yet how they could flash when her impetuous nature was aroused by some unkind act or unfair word said or done against anyone she loved. Her's was the outstanding personality of the six girls. Her only fault (which in later years was the cause of untold sorrow) was the spirit that was too proud for her own welfare. Dear Aunt Tamer, I have felt that you were born far ahead of your time. You belonged in the modern trend of things. The women of your day weren’t meant for the spirited independence and spunk that God gave to you.

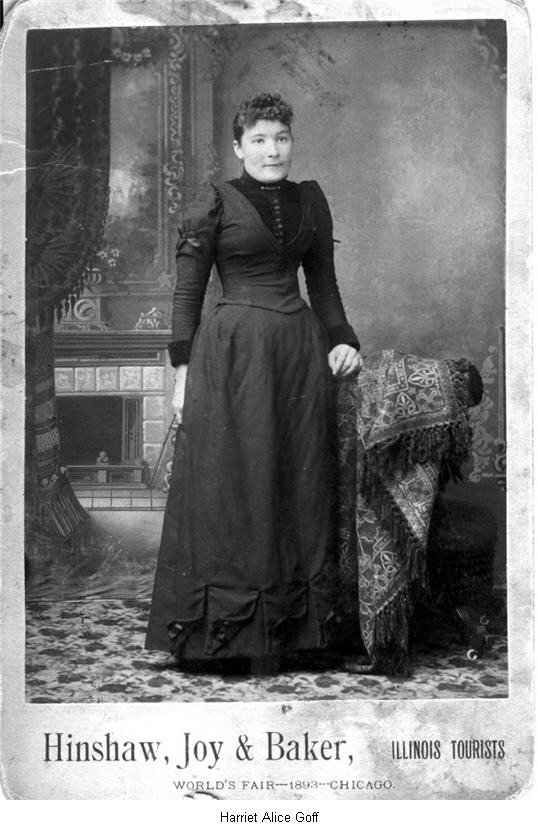

Next comes Harriet, a noble woman with sterling characteristics and high ideals. No one ever visited Aunt Harriet without coming from her home feeling uplifted and benefited. She had a steadying influence that gave out strength and courage.

Ginnie, the baby girl of the family, was a lovely person. Her naturally wavy brown hair and dark eyes and ever-ready smile made her well liked by all who knew her. She was easier going than the other sisters. She trusted everyone and was never happier than when she was going to call on folks or when visiting her family.

The men of the family who lived to maturity were Heber, who had reddish brown hair, very curly, and he always wore a beard, and Joseph, who looked much like Heber with the exception of no beard. Last of all came Isaac, replica of his father’s sandy hair, blue eyes and light skin. He was a lonely man since he never married and never left the farm or his mother’s house as long as she lived.

Joseph was blessed with a fine tenor voice and he and his sisters Tamer and Harriet formed a trio that, for harmony and tonal quality of voice, was hard to beat. Beloved songs and hymns of the Church were sung by this trio at weddings, picnics and parties of the day.

I started out to write about Grandmother, so back to her. She must have been a beautiful young girl because she was still beautiful as far back as I remember her. She was about five feet two, her face was small featured, her hair and eyes dark brown, her complexion was fair with perpetual maiden blush roses on her cheeks, even until the last year she lived.

What a treat to go visiting to Grandmother’s. We would walk along the railroad track until we came to the lane that led to the adobe house with walls one and one half feet thick, floors of pine boards a foot in width. The windows were set in the deep walls, their sills making a wonderful place that was always filled with Grandmother’s potted plants. No curtains were every used in her large, homey kitchen. Grandmother had the proverbial green thumb, these potted geraniums white, pink and red; her favorite being the ivy and Martha Washington geranium. These being set off by the margariettes, fucias, dew plants, Star of Bethlehem, yellow, white and pink oxalis, and other old favorites.

The soil that she used when setting out a new plant (usually a slip) had to be thoroughly heated in the oven, which she said destroyed all worms and bugs, yet never hurt any of the minerals in the soil. In winter she melted snow, which she used to water her plants and, come spring, a large barrel set under the drain pipe at the southeast corner of the house was filled when the spring and summer rains fell. This rainwater was carefully hoarded for the watering of plants and for washing the hair.

The kitchen floor was bare and scrubbed white. Clean sand was used to scour it, then it was washed with suds made from yellow homemade soap.

Colorful scatter rugs made from a burlap sack, to which rags cut in even lengths about six inches long and one and one half inches wide were pushed through the sack by a sharpened wooden peg. These rags were pulled through in rows, the bright reds, plaids or greens for the center, finished by several rows of black or darker colors forming the border.

White washed walls, a shiny black stove with side oven doors, later replaced by the luxurious Home Comfort range, and white checked table cover with a fringe on for in between meals, a cupboard, a lounge, a clock placed on a wall shelf, a corner set aside for water bucket, wash basin, coal scuttle and shovel, kitchen chairs, and an old armed rocking chair and a never to be forgotten framed picture of the “Old Rugged Cross”, which hung on the wall above the lounge.

On every wall in the room were pictures or rather enlarged photographs of her mother, sisters, and other loved members of the family. Pennies, nickels and dimes must have been saved for a long time in the old sugar bowl to have acquired enough money to pay for these enlargements. I shall never forget how grand that room seemed to me every time I entered it. Grandmother died in that room and she looked just as elegant as she lay at rest there the morning of her funeral.

Grandmother’s large bed-sitting room contained a large hand carved bed, a dresser or bureau to match, six chairs with knitted tidies tied over the backs with blue satin ribbon, two antique round center tables, and several rocking chairs. The floor was covered with a woven rag rug or carpet made from balls of rags sewed and woven into long strips, which were woven with red, green, yellow and black carpet warp. Snowy white Nottingham lace curtains hung from the two large windows.

In those days shopping trips were very few and far between, so her food supply came mostly from a large dirt roofed cellar. A trip to the cellar was something to fill the soul with delight. Deep, dark and cool that cellar was; dug down into the earth, you came into it after undoing the padlock attached to the outside doorway, then going down six plank steps. Hams and sides of bacon that she had sugar cured, hung from the rafters of the roof.

Along the wall on one side was a long plank shelf upon which rested large pans of milk covered over with a length of white mosquito netting which hid and protected the thick layers of golden yellow cream. At the far side were the cream crock and the wooden dash churn. Pounds of delicious golden butter she churned and printed in a round, one-pound butter mold, which had a pineapple design carved into the bottom mold. This stood up in a beautiful pattern when the butter was set out on the butter tray.

Along the other two sides of the cellar were rows and rows of Grandmother’s pickles. Oh, those spiced pickled onions, large as hen’s eggs, put up in plain vinegar, crisp red cabbage, pickles in stone crocks, mixed sweet mustard pickles and other varieties.

The preserves: crabapple, pear, black currant, apple, pickled peaches (all preserved with whole cloves and cinnamon sticks). Red currant, chokecherry and pottawattomie plum jelly all stored in small crocks and glasses and sealed by a thick layer of sugar sprinkled over the top then each container with a brown paper cap and then, over the paper cap, an old piece of clean cloth was tied on with string.

The fresh fruits were lined up in rows of glass Mason jars with zinc caps and rubber bands. There was always the old standby of dried fruits and the large can of honey, gallons of it. Grandmother used to break of small chunks of honey for each of us, but because of the tickling sensation it made in our throats we were never able to swallow the luscious morsels.

The trip to the cellar, as you may have guessed, preceded the usual tea Grandmother always prepared in the afternoon. The tea she served us was made with hot water and creamy milk and flavored with sugar and some kind of spice. She said it warmed up the stomach and it seems to me it did more than that, as it warmed the heart with kindness and love. The love in her eyes, the feel of her hand laid caressingly on our heads felt like a blessing or benediction. With the tea, there would be homemade bread, nippy cheese, samples of the pickles, preserves and honey.

The best of all the treats was some raisin loaf bread made from regular bread recipe sweetened and filled with raisins, currants, citron, lemon peel, caraway seeds and spices. No one has ever made raisin bread like dear little Grandmother Goff used to make.

Grandmother never had luxuries; she was content with simple things. At one time, when Grandfather made a trip to Salt Lake City by team and wagon, he brought back a chest filled with real nice things, a dress length for Delane (flowered material), for the four girls, Naomi, Tamer, Harriet and Ginnie, a real paisley shawl, some real Irish linen table cloths and napkins, yards of cambric, laces and embroideries.

As a young girl and after her marriage, Grandmother worked in a glove factory in England, sewing the fine seams of kid gloves. She had had no opportunity to go to school and therefore, was unable to read. After her children were all married and Grandfather had passed on, she tried to read the newspaper and church periodicals, and by the blessings of her Heavenly Father a great gift was given to her. For after reaching over fifty years of age, she learned to read and a new world of understanding was opened up for her lonely years. Grandmother told this to me and said it was the greatest testimony of her life as learned to pick out the meaning of the words.

When the family was all teenagers, Grandfather (Thomas Goff) decided to build a home as they were then living in a two-room log cabin. So in the time between the heavy labor of the farm, the children all had to find time to make adobe bricks. These bricks were made from clay mixed with straw and sand and dried in the sun until they were ready to be used in the construction of four large rooms. This house still stands in west Sandy. Within its walls the girls had their wedding receptions, parties, family gatherings, threshing days when the men who came to do the threshing were fed three substantial meals a day and the threshing lasted several days because the farms contained many acres that had yielded hundreds of bushels of golden grain, which was stored in huge bins in a granary. The straw which was clean and shining was used as fodder for the cows, horses and hogs, for chicken coops, in the pits that were used to store potatoes, winter vegetables, and apples. This new straw was also used as a mat under the rag carpets and in ticks used as a mattress on the beds.

The front door of this home was used to bring out the cold silent forms of Grandfather in August 1890 and Grandmother on 12 December 1912.

Grandmother sailed from Liverpool, England on the ship American Congress on 23 May 1866. She and her husband, Tom, and their four children arrived in Salt Lake City on 1 October 1866 with Captain Joseph S. Rawlins’ ox train.

Grandfather Goff was ill most of the way. Sometimes he rode; a few times he walked along with Grandmother helping him. Because of this they were left far behind the wagon train.

(I might mention here that Isaac Goff, his wife Mary Naylor Goff and family, who was the father of Thomas Goff sailed on the ship Cynosure from Liverpool, England on 30 May 1863 and arrived in Great Salt Lake as members of Captain Rosel Hyde’s Company on 13 October 1863.)

One day when they were quite a distance behind the wagon train some Indians suddenly rode up to them. Grandmother was terrified and felt they would be killed. The old chief or the leader looked shrewdly at them. He could speak a few words of English and after scrutinizing Grandfather very thoroughly he said, “White man sick, much sick.” Then, reaching into his shirt or whatever he was wearing, he brought out a small leather pouch, which he handed to Grandfather saying, “Make-um tea for white man.” The pouch contained some dried herbs. They then departed as suddenly as they had come leaving Grandmother free to continue on her wearisome way in the gathering dusk of the coming night.

When they finally reached the valley of the Great Salt Lake, their first home was a dugout near the Jordan River in what was then Bingham Junction (later Midvale). This dugout was on the hillside where the concentrate mill in Midvale is now located, just south of the D&RG Railroad underpass.

One day while they were living here my mother, then a child of three or four, sat on a little stool watching Grandmother scrape live embers into a pile in preparation to bake bread in an iron Dutch Oven. Mother must have become drowsy and she fell forward into the hot coals, burning the right side of her neck and lower part of her cheek. She carried these scars as long as she lived.

During the first trying years when they were so desperately trying to make a livelihood, Grandmother and her girls went into the wheat fields, gleaned the wheat, flayed the golden kernels, gathered them and took them to the mill, received flour in exchange, which she took home and mixed into bread all in the same day. (By gleaning it meant the people had permission to go to the wheat fields and to gather the heads of grain that had been left by the reapers, who cut and tied the grain into bundles.)

For a hot morning drink they burned bread crusts and sometimes wheat kernels, which they boiled, and to the water, which was drained off, they added milk, cream or any kind of sweetening they were lucky enough to have. They also drank sunflower tea as a medicine.

Although Grandmother remained true and faithful to her religion until her death, she could not accept polygamy. She said she felt she couldn't live in plural marriage. She was not a selfish woman, neither was she aggressive. I remember her always as a meek and obedient wife, yet she had a deep inner strength of purpose that was unwavering and truthful to the high ideals she set for herself. When her husband’s mother decided that the time had come for Tom to take a second wife, she immediately called on Grandmother to tell her of this arrangement. Grandmother listened dutifully to all that her husband’s mother had to say then, arising without a word, she left the room and walked out onto the porch. Silently she stood there, her eyes gazing fixedly at the Jordan River flowing along one half mile to the west. Then she turned and walked slowly back into the kitchen and standing before her mother-in-law she said, in a calm, determined manner that the day that Tom brought another wife into the home that she had slaved for, then that was the day that she would walk down to the Jordan River and wade out into the stream never to return. She reminded her mother-in-law that she had taken care of her husband Tom during the complete journey across the plains and that she had seen her daughters daily doing men’s work in the fields in order to help their father establish a home and a homestead and that she could not share him with another woman. For weeks she was a sad and forlorn little figure, never speaking, eating or sleeping, just quietly brooding until at last Grandfather went to see his mother, telling her that he couldn't hurt Harriet like that any longer because he truthfully didn’t want another wife as he wasn't able to support the one he already had in the manner that he would like to. Whether what she did was right or wrong, I can’t say. Her family knew she wasn’t putting on an act and they felt she would not have wavered in her determination to take her own life.

When death claimed her second little daughter and friends came to stand by to offer their sympathy and condolences as she stood near the little white cotton lined pine box that held the still little form within, she said, “It’s all right. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.”

Since I have tried to give a true picture of the trials, fortitude and the fine qualities of motherhood that Grandmother possessed, the following incident perhaps will serve to show a little bit of the humorous side of her life. Grandfather was the water master for a few years and he sometimes stayed too long on his route enjoying a few drinks with the sociable fellows in Sandy. He came home one night a little too much under the influence of stimulants. Grandmother in a flash of indignant anger said, “I wish your guts would bust!” Grandfather had placed a large red apple inside his vest as a gift for her. No sooner had the words left her lips than he opened his vest so that the red apple showed through the opening. He then gave an awful groan and fell limply to the floor gasping, “Well, my dear, for once you shall have your wish.” Grandmother was really frightened by her rash talk and quickly did everything she could to let Grandfather know she did not really mean what she had just said.

In her later years she loved to raise turkeys. It used to be quite a sight seeing those huge birds roosting on the sheds and in the long row of apple trees along the ditch banks. One year she had a fierce old turkey gobbler who would become so enraged his head and wattles became bluish purple. His eyes glistened with malice, his tail feathers spread out like a fan, his feathers ruffled, his wings scraping up the dust as he strutted and chortled. He made quite a majestic figure from a safe distance. When he came tearing toward us we became weak with fright and we tried to keep out of his sight.

Grandmother on one occasion and during Thanksgiving time sent her daughters to Salt Lake City with eight or more of her finest turkeys in the wagon which Grandfather had hitched up before daylight. One turkey was to be given for tithing and the girls were to each have the material for a dress from the money they received from the sale of the other birds. The dresses were chosen from the same bolt of cloth and were to be all alike, until mother found a way to add different touches of trimmings to each one. What a chore it was making a dress in those days. All skirts had to be lined and the Basques boned. Pleats, folds and other furbelows all had to be added as the dresses were very dressy and fancy. Bustles, crinolines and high choker collars, also wide sashes and the inevitable Warner corset were all necessary for each new gown. It took weeks sometimes to complete one dress. Mother (Naomi) at one time sewed these dresses by hand, later she used a sewing machine.

It was customary for the ladies, young and old, to have their ears pierced in anticipation of their wearing earrings. The young men of their choice invariably gave his lady a set of earrings, either as an engagement present or wedding gift. Ruth was the official ear piercer, which was quite a procedure. The ear lobe was pinched until it became quite numb; then a burned cork was placed at the back of the ear lobe, a sterilized, heated needle was then thrust through the ear lobe until it went into the cork. Then, a broom straw was inserted through the newly pierced hole and left there until the swelling had gone and the wound had healed. If the girl with the newly pierced ears hadn’t earrings, there the straw remained in the ear lobe to prevent the hole from healing and closing.

In closing I have written a few lines of verse, which I think is befitting of Grandmother.

Grandmother Mine

Harriet Smith Goff

I don’t know of anything I’d rather do

Than to sit in reminiscence

Dear Grandmother of you

You were so kind and ever so quaint

To me you seemed always a saint

Dear Grandmother mine

With your eyes ashine.

I don’t know of anything I remember so well

As when I sat by your side

And listened to the tales you would tell

Of the brave pioneers

Oh! Grandmother mine

With your smile divine

Do you think that I, if put to the test

Could leave far off England and all I loved best

As you have done

In your way so fine

Blessed grandmother of mine

May I honor the birthright you gave to me

And the ideals so dear to your heart

Striving always to be worthy of your blessing

As my years decline

Beloved grandmother of mine.

Gertrude Hardcastle Beckstead

September 20, 1952

Editor's Notes

This document is the most recent of many editions.

- Kory L. Ainsworth transcribed and edited parts 1 and 2 of this document on 18 August 2001. He edited part 3 on 27 November 2001. He added and edited part 4 on 16 December 2001.

- The source document for parts 1 and 2 was a typed transcript created many years ago by his mother, L. Jane (Goff) Ainsworth, a Goff descendent.

- The source document for part 4 was a typed transcript created about 1990 by Cindy (Jensen) Goff, daughter-in-law of Ielo and Grace Goff, married to Michael.

This edition contains many corrections of spelling and grammar from the original documents, but great effort has been made to maintain the content and context of the original narrative.

Return to Goff History - Part 1Continue to Goff History - Part 3

Gallery

Videos

- There are no videos available at this time.